Why Kwashiorkor Matters

The Paradox

A deadly protein deficiency that defies simple explanations

Severe Acute Malnutrition

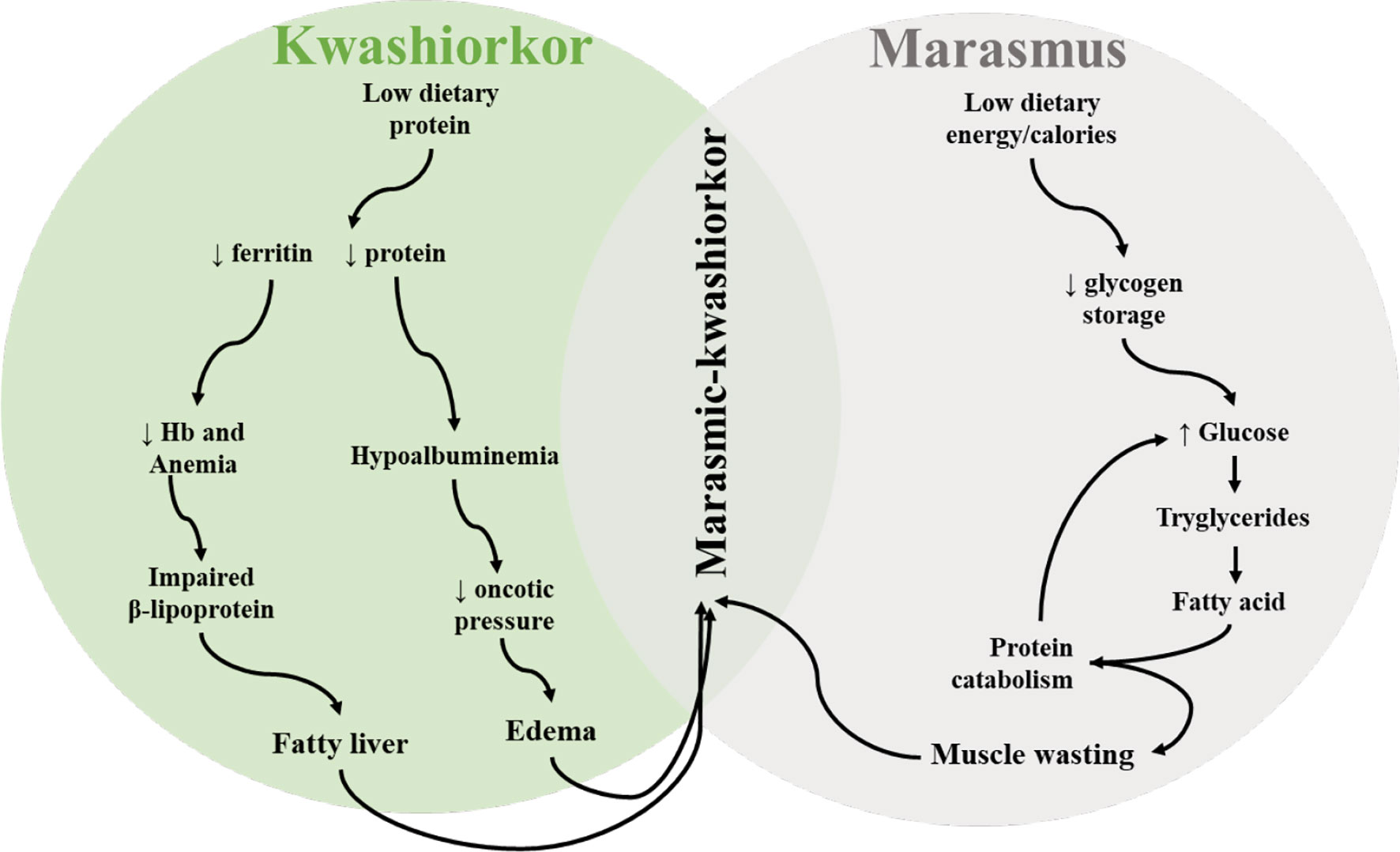

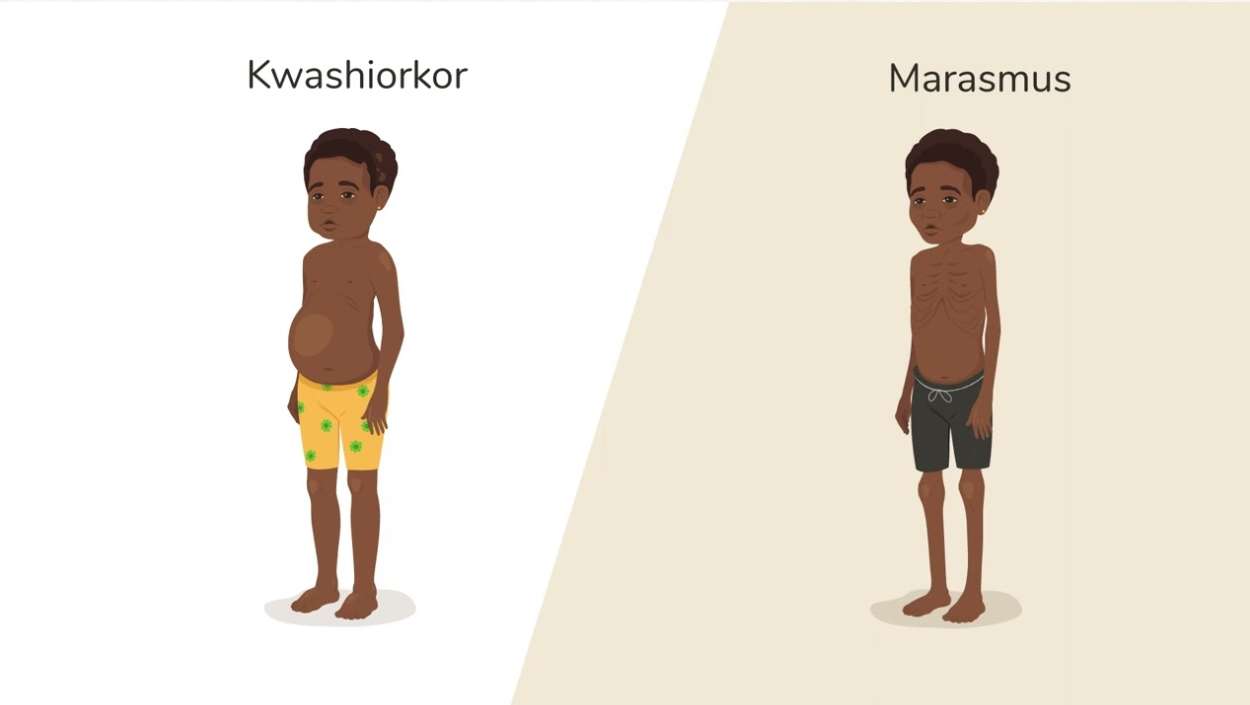

Kwashiorkor is characterized by edema (fluid retention), despite adequate caloric intake in many cases.

Unlike marasmus (pure caloric deprivation), kwashiorkor patients often consume sufficient carbohydrates but lack high-quality protein.

The Clinical Puzzle

Children with similar caloric intake can have vastly different outcomes - some develop kwashiorkor, others remain healthy.

Beyond Protein

Protein deficiency alone doesn't explain kwashiorkor - genetics, epigenetics, and the microbiome all play crucial roles.

"The Disease of the Deposed Child"

"The sickness the baby gets when the new baby comes"

First named by Dr. Cicely Williams in 1935, the term reflects a tragic reality: when a new sibling arrives, the older child is weaned from protein-rich breast milk onto a carbohydrate-heavy diet of maize, cassava, or rice — foods that fill the belly but starve the body of essential amino acids.

Global Health Crisis

Kwashiorkor affects millions of children in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia annually.

Protein Biochemistry

Demonstrates how protein deficiency disrupts protein synthesis pathways at the molecular level.

Complex Etiology

Illustrates the intersection of nutritional genomics, metabolomics, and microbial ecology.

Connection to Protein & Amino Acid Structure

→Amino acid pool insufficiency causes liver to prioritize acute phase proteins over albumin

→Essential amino acid deficiency impairs protein synthesis pathways

→Methionine/cysteine scarcity leads to glutathione depletion and oxidative stress

→Leucine/methionine deficiency downregulates mTORC1 signaling, suppressing growth

→Apolipoprotein synthesis failure impairs triglyceride export, causing fatty liver

→One-carbon metabolism disruption creates epigenetic changes

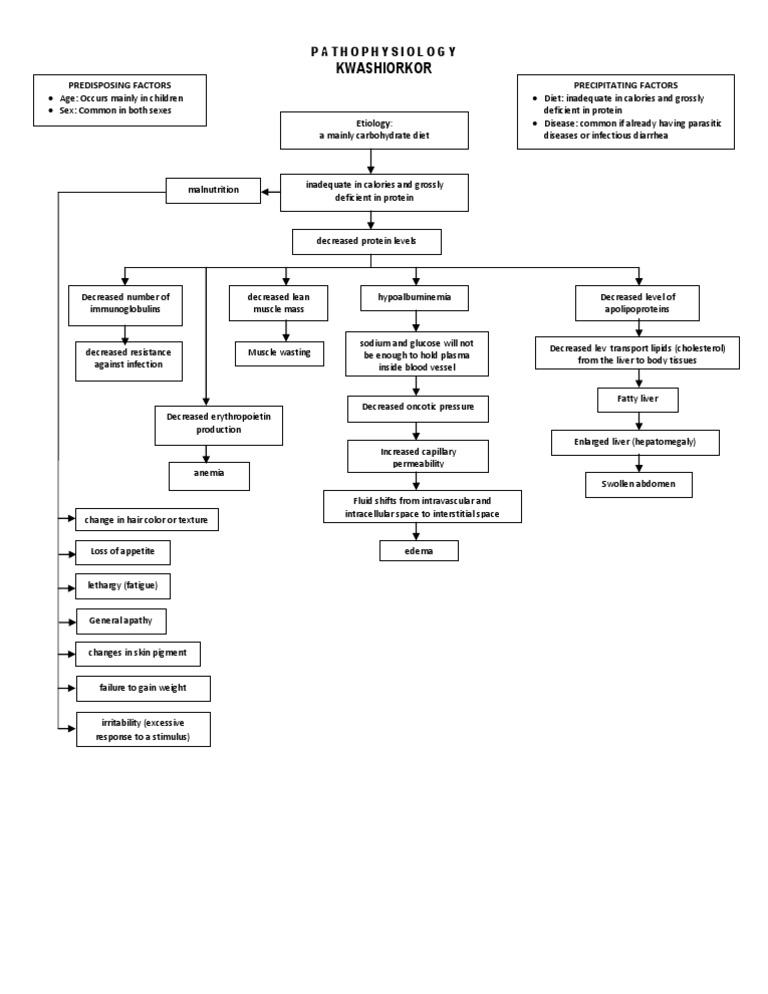

Pathophysiology: Five Critical Pathways

Protein deficiency cascades through multiple organ systems, creating a web of interconnected metabolic dysregulation

Predisposing Factors

- •Age: Mainly children 1-5 years (post-weaning)

- •Sex: Affects both sexes equally

Precipitating Factors

- •Diet: Inadequate calories, grossly deficient in protein

- •Infection: Parasitic diseases, infectious diarrhea (especially measles)

- •Socioeconomic: Famines, displacement

Carbohydrate-Heavy Diet Connection

Diets based on maize, cassava, or rice are frequently associated with kwashiorkor:

Low Protein Quality

Deficient in essential amino acids like lysine, tryptophan

Near-Adequate Energy

Prevents pure wasting of marasmus

Low Sulfur Amino Acids

Methionine, cysteine needed for antioxidant defenses

Visualization Options

Pathophysiology: Kwashiorkor

Etiology

Mainly carbohydrate diet

Inadequate in calories and grossly deficient in protein

Learning Objective: Predict consequences that result from defects in specific metabolic pathways, including vitamin and macronutrient deficiencies.

Clinical Manifestations: A Three-Way Comparison

Understanding kwashiorkor requires comparing it to both healthy states and other forms of malnutrition

Three-Way Comparison

| Feature | Healthy Individual | Marasmus | Kwashiorkor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Intake | Adequate for growth | Severely deficient | Adequate or near-adequate |

| Protein Intake | Adequate, balanced amino acids | Severely deficient | Severely deficient relative to energy |

| Body Appearance | Normal growth and muscle tone | Severe wasting ("skin and bones") | Edematous, rounded face, swollen limbs |

| Edema | None | None | Present - pitting edema |

| Liver Function | Normal metabolism | Increased fatty acid oxidation | Impaired lipoprotein synthesis → fatty liver |

| Serum Albumin | Normal (3.5–5.0 g/dL) | Mildly decreased | Markedly decreased (<2.8 g/dL) |

| Hormonal Profile | Balanced insulin, cortisol, GH | Low insulin, high cortisol (catabolic) | Higher insulin (from carbs), suppressing lipolysis |

| Oxidative Stress | Controlled antioxidant defense | Moderate oxidative stress | Severe (low methionine/cysteine → glutathione depletion) |

| Immune Function | Intact | Impaired | Severely impaired; infections common |

| Hair & Skin | Normal pigmentation, texture | Thin, dry hair and skin | Depigmentation ("flag sign"), flaky paint dermatitis |

Clinical Presentations

← Use arrows or swipe to compare clinical presentations →

Kwashiorkor Features

- •Edema: Swollen abdomen, puffy face, pitting edema in legs

- •Skin changes: “Flaky paint” dermatitis, depigmentation

- •Hair: Color changes (flag sign), thin, easily pluckable

- •Hepatomegaly: Enlarged, fatty liver

- •Behavior: Apathy, lethargy, irritability

Marasmus Features

- •Wasting: Severe muscle and fat loss (“skin and bones”)

- •No edema: Thin, visible bones

- •Sunken face: “Old man” appearance

- •Normal liver: Active fatty acid oxidation

- •Behavior: Alert but weak, irritable

Why the Difference?

Kwashiorkor

Diet: Near-adequate energy (carbs) + severely deficient protein

Hormones: Insulin relatively higher (from carbs) → suppresses proteolysis and lipolysis

Result: Edema (low albumin), fatty liver (can't export lipids), preserved fat stores

Marasmus

Diet: Severely deficient in BOTH energy and protein

Hormones: Low insulin, high cortisol (catabolic state) → active proteolysis and lipolysis

Result: No edema, extreme wasting, active fat oxidation for energy

Nutritional Genomics in Kwashiorkor

In the same village, eating similar diets, exposed to similar infections — some children develop kwashiorkor while others remain healthy. Why?

Child A: Healthy

- ✓Same diet (maize-based)

- ✓Same village environment

- ✓Similar infection exposure

- ✓Different outcome: Remains healthy

Child B: Kwashiorkor

- ✓Same diet (maize-based)

- ✓Same village environment

- ✓Similar infection exposure

- ✓Different outcome: Develops kwashiorkor

Answer: Genomic & Epigenetic Differences

Genetic variants and epigenetic modifications create differential susceptibility to kwashiorkor even under identical environmental conditions.

Polymorphisms in Antioxidant Genes

SOD2

GPX1

CAT

Interactive: Genotype Outcomes

mTORC1 Signaling Dysregulation

Normal State

- →Amino acids (leucine, methionine) activate mTORC1

- →mTORC1 promotes protein synthesis, cell growth, immune function

Kwashiorkor State

- →Inadequate amino acids downregulate mTORC1

- →Result: Suppressed growth, impaired repair, immune dysfunction

⚠Emerging Research Area

KwashNet (NIH-funded initiative) is conducting the first large-scale human genetic studies to identify genetic loci underlying differential susceptibility to kwashiorkor. Initial meetings held in Botswana (2023) and Uganda (2024).

Note: Specific genetic variants (SOD2, GPX1, CAT) presented here are based on conceptual understanding of antioxidant gene polymorphisms in malnutrition. Direct evidence specific to kwashiorkor awaits publication of KwashNet findings.

Learning Objective: Describe basic concepts of nutritional genomics. Predict how genetic variations in enzymes, nutrient transporters or regulators could affect human health and disease.

Research Note: Sources & Emerging Areas

Research Note

This presentation synthesizes evidence from peer-reviewed sources with emerging research on genetic, epigenetic, and microbiome factors in kwashiorkor.

✓Well-Supported Content

- •Clinical features & pathophysiology → Benjamin & Lappin, StatPearls 2023

- •Geographic clustering in DRC → Fitzpatrick et al., Food & Nutrition Bulletin 2018

- •Twin study microbiome findings → Smith et al., Science 2013

⚠Emerging Research Areas

- •Antioxidant gene variants → Ongoing KwashNet research, not yet published

- •Precision nutrition strategies → Experimental approaches, not standard of care

- •Community-level factors → Hypotheses requiring investigation

Genetic Research Status

KwashNet (NIH-funded initiative) is conducting the first large-scale genetic studies to identify genetic loci underlying kwashiorkor susceptibility. Initial meetings held in 2023-2024, but published results are pending.

Treatment Efficacy Note

RUTF non-response rates vary by context (reported 7-15% in recent studies). Relapse rates are significant but depend on follow-up duration, socioeconomic factors, and access to continued care.

Learning Objective: This presentation demonstrates how cutting-edge research integrates protein biochemistry with genomics, metabolomics, and microbiology to address complex nutritional disorders.

Microbiome and Metabolomics

The Malawian Twin Study

Landmark Research (Smith et al., Science 2013): Studied 317 Malawian twin pairs during first 3 years of life. 43% became discordant for acute malnutrition—despite identical genetics and household diet. Gut microbiome composition differed dramatically between affected and healthy twins.

Monozygotic (identical) twins

Same household, same meals

Gut microbiome composition differed dramatically

Microbiome Dysbiosis in Kwashiorkor

Healthy Children

Diversity

High (>200 species)

Dominant Phyla

Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes (beneficial)

SCFA Production

High (butyrate, propionate)

Amino Acid Synthesis

Robust (esp. lysine, B vitamins)

Kwashiorkor Patients

Diversity

Low (<100 species)

Dominant Phyla

Proteobacteria (pathogenic)

SCFA Production

Severely reduced

Amino Acid Synthesis

Impaired

Metabolomic Signatures

Depleted Metabolites

- •BCAAs: Leucine, isoleucine, valine

- •Aromatic AAs: Tryptophan, phenylalanine

- •Antioxidants: Reduced glutathione (GSH), vitamin E

Elevated Metabolites

- •Inflammatory markers: CRP, pro-inflammatory cytokines

- •Oxidative stress: Lipid peroxides, protein carbonyls

- •Gut permeability: Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), zonulin

The Microbiome-Nutrition Axis

📊Metabolomic Data Source Note

Specific metabolomic signatures (BCAAs, glutathione, LPS, zonulin) are synthesized from multiple studies on severe acute malnutrition. Research confirms glutathione depletion (Badaloo et al., 2002) and sulfur amino acid deficiency (Gonzales et al., 2021) in kwashiorkor populations.

Clinical Implication

Protein supplementation alone may fail if gut microbiome is not restored.

Geographic Distribution: The Village-Level Crisis

The Fitzpatrick Study: Eastern DRC, 2018

Children aged 12-59 months

Villages in single 4km × 4km health area

Census (not sample) — every child

The Hidden Crisis

Village-Level Reality

Range across villages

Highly significant clustering

High-Prevalence Villages

Average prevalence in top 5 villages

Total kwashiorkor cases concentrated here

303 children screened

Low-Prevalence Villages

Prevalence in bottom 5 villages

Zero cases despite similar population

335 children screened

Hypothesized Community-Level Factors(Under Investigation)

Note: Fitzpatrick et al. (2018) documented clustering patterns but did not identify underlying causes. These factors represent hypotheses requiring investigation. Aflatoxin has been investigated but shows inconsistent associations.

Water Source

Contamination differences?

Food Taboos

Local dietary practices?

Soil Minerals

Crop nutrient deficiencies?

Genetic Clustering

Shared susceptibility?

Endemic Infections

Parasites, pathogens?

Aflatoxin Exposure

Grain storage practices?

Public Health Implications

What This Means:

- →Village-to-village comparisons can identify protective factors

- →Targeted interventions more cost-effective than broad programs

Research Opportunities:

- →Novel, durable, low-cost solutions based on local protective factors

- →Precision public health interventions

Public Health Implications and Interventions

Current WHO Guidelines

F-75 Formula

F-100 Formula

RUTF

Limitations of Standard Treatment

Non-response rates to RUTF (varies by context)

Relapse rates (affected by poverty, access to care)

Does not address microbiome or genetic factors

New Paradigm: Precision Nutrition(Experimental)

⚠Current Standard of Care

WHO-recommended treatment remains F-75/F-100 formulas and RUTF. Precision nutrition approaches (probiotics, targeted amino acids, epigenetic interventions) represent emerging research areas not yet validated as standard of care. Clinical trials are ongoing.

Policy Recommendations

For Malnutrition Programs:

- →Integrate microbiome diagnostics into SAM screening

- →Develop village-specific interventions based on local clustering patterns

- →Invest in clean water and sanitation infrastructure

For Research:

- →Fund longitudinal microbiome studies in high-risk populations

- →Establish biobanks for genomic and metabolomic research

- →Conduct randomized controlled trials of synbiotic + RUTF combinations

Key Takeaways

Five essential insights that reframe kwashiorkor from simple protein deficiency to a complex multi-system disorder

Protein Deficiency Is Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Kwashiorkor requires protein deficiency, but additional factors determine who develops the disease:

- •Genetic polymorphisms in amino acid metabolism

- •Epigenetic dysregulation via one-carbon metabolism

- •Gut microbiome dysbiosis

Five Interconnected Pathways

Immune, Hematologic, Muscle, Edema, Hepatic—all stem from inadequate amino acids, but they amplify each other through:

- •Inflammation → increased protein catabolism

- •Oxidative stress → further immune suppression

- •Fatty liver → impaired nutrient transport

The Microbiome Is a Key Player

- •Discordant twins with identical genetics and diets show different microbiomes

- •Dysbiosis reduces amino acid synthesis and increases gut permeability

- •Microbiome restoration may be critical for recovery

Geographic Clustering Demands Targeted Interventions

- •Village-level variations (0% to 14.9%) suggest local, non-dietary factors

- •Precision public health: Focus resources on high-risk communities

- •Investigate water, sanitation, and cultural food practices

The Future Is Precision Nutrition

Beyond one-size-fits-all RUTF:

- •Personalized protein requirements based on genetics

- •Synbiotics to restore healthy microbiomes

- •Methyl-donor nutrients (folate, B12, choline) to reverse epigenetic damage

Discussion Questions

Questions to guide peer review and class discussion. Click each card to expand.

These questions connect protein biochemistry to real-world public health challenges.

References

Primary and supporting sources used in this presentation

Primary Sources

Benjamin O, Lappin SL. Kwashiorkor. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jul 17. PMID: 29939688. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507876/

Fitzpatrick M, Ghosh S, Kurpad A, Duggan C, Maxwell D. Lost in Aggregation: The Geographic Distribution of Kwashiorkor in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(4):512-520. doi:10.1177/0379572118794072

Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, et al. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339(6119):548-554. doi:10.1126/science.1229000. PMID: 23363771; PMCID: PMC3667500.

Supporting Research

Badaloo A, Reid M, Forrester T, Heird WC, Jahoor F. Cysteine supplementation improves the erythrocyte glutathione synthesis rate in children with severe edematous malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(3):646-652. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.3.646. PMID: 12198014.

Gonzales GB, Njiti V, Singa JG, et al. Dietary intake of sulfur amino acids and risk of kwashiorkor malnutrition in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(4):e13191. doi:10.1111/mcn.13191. PMID: 33840157; PMCID: PMC8435999.

Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. J Nutr. 2006;136(1 Suppl):227S-231S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.1.227S. PMID: 16365087.

Saad MJA, Santos A, Prada PO. Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Physiology. 2016;31(4):283-293. doi:10.1152/physiol.00041.2015. PMID: 27252163.

Desyibelew HD, Fekadu A, Woldie H. Recovery rate and associated factors of children age 6 to 59 months admitted with severe acute malnutrition at inpatient unit of Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral hospital therapeutic feeding unite, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171020.

Ongoing Research Initiatives

National Human Genome Research Institute. Kwashiorkor Collaborative Network (KwashNet). Available from: https://www.genome.gov/research-at-nhgri/projects/KwashNet

Note: First large-scale human genetic studies of kwashiorkor susceptibility. Inaugural meetings held 2023-2024, published results pending.

Genton L, Cani PD, Schrenzel J. Alterations of gut barrier and gut microbiota in food restriction, food deprivation and protein-energy wasting. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(3):341-349. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2014.10.003.

Additional Resources Consulted

- •World Health Organization. Guideline: Updates on the Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

- •Trehan I, Goldbach HS, LaGrone LN, et al. Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):425-435.

- •Manary MJ, Sandige HL. Management of acute moderate and severe childhood malnutrition. BMJ. 2008;337:a2180.

Presentation prepared for NUTR 630: Protein and Amino Acid Structure and Properties

University of Michigan School of Public Health | November 2025

NUTR 630 - Protein and Amino Acid Structure and Properties • Dr. Bridges

University of Michigan School of Public Health • M.S. Nutritional Sciences